How and Why Does Dropout Work?¶

What is Dropout?¶

The idea behind dropout is quite simple - during the training phase, a randomly selected subset of neurons is “dropped out” of the computation. This is achieved by setting their activations to 0. A fixed proportion \(p\), usually between 10-50%, are “dropped out” during each training step. This value is often different for each layer.

During the testing phase, dropout is not applied, but instead, the outputs of each layer are scaled down by a factor of \(1-p\).

Empirically, this results in improved generalization performance (i.e. on the validation or test set).

In this experiment, we will compare two deep neural networks, one without dropout and one with. Then, we will try to understand why dropout results in better performance.

Let’s Start by Loading the CIFAR-10 Dataset¶

The CIFAR-10 dataset is a popular benchmark for machine learning and computer vision tasks, consisting of 60,000 32x32 color images across 10 distinct classes. Each image is labeled as one of the following categories: airplane, automobile, bird, cat, deer, dog, frog, horse, ship, or truck. The dataset is divided into 50,000 training images and 10,000 test images, with an even distribution of 6,000 images per class.

Despite its simplicity, the dataset contains a variety of object poses, lighting conditions, and backgrounds, making it non-trivial to achieve high accuracy.

Typicall, Convolutional Neural Networks and other image-specific architectures are used for this dataset. However, for this experiment, we will use a feedforward network in order to demonstrate the benefits of using dropout.

Show code cell source

import tensorflow_datasets as tfds

import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

train_tf, test_tf = tfds.load('cifar10', split=['train', 'test'], batch_size=-1, as_supervised=True)

raw_train_images, train_labels = train_tf[0], train_tf[1]

raw_train_images = jnp.float32(raw_train_images)

raw_train_images = raw_train_images.reshape((raw_train_images.shape[0], -1))

train_labels = jnp.float32(train_labels)

raw_test_images, test_labels = test_tf[0], test_tf[1]

raw_test_images = jnp.float32(raw_test_images)

raw_test_images = raw_test_images.reshape((raw_test_images.shape[0], -1))

test_labels = jnp.float32(test_labels)

print(f"Training Set Size {raw_train_images.shape[0]}")

print(f"Test Set Size {raw_test_images.shape[0]}")

Training Set Size 50000

Test Set Size 10000

What Does Our Dataset Look Like?¶

Let’s look at a few training examples.

Show code cell source

from IPython.display import display, HTML

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import math

plt.style.use('seaborn-v0_8-darkgrid')

RANDOM_KEY = 42

num_examples = 25

row_size = int(math.sqrt(num_examples))

fig, axs = plt.subplots(row_size, row_size, figsize=(row_size,row_size))

rng = jax.random.PRNGKey(RANDOM_KEY)

idxs = jax.random.randint(rng, (num_examples,), 0, raw_train_images.shape[0])

exs = raw_train_images[idxs,:].reshape((num_examples,32,32,3))/255.0

for ex in range(num_examples):

i = ex // row_size

j = ex % row_size

axs[i,j].imshow(exs[ex])

axs[i,j].set_xticks([])

axs[i,j].set_yticks([])

axs[i,j].set_xmargin(0)

axs[i,j].set_ymargin(0)

plt.show()

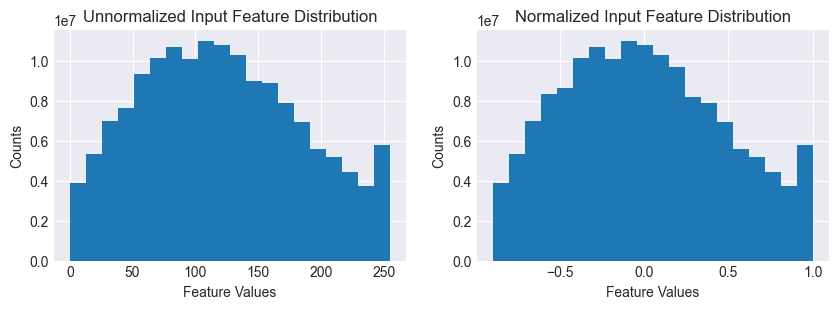

Let’s now preprocess the dataset and look at the input feature distrubition.

Show code cell source

# First, let's plot the histogram for the unnormalized dataset

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1,2, figsize=(10,3))

axs[0].hist(raw_train_images.flatten(), bins=20)

axs[0].set_title("Unnormalized Input Feature Distribution")

axs[0].set_xlabel("Feature Values")

axs[0].set_ylabel("Counts")

# Let's normalize the dataset

train_mean = raw_train_images.mean()

train_std = raw_train_images.std()

train_images = (raw_train_images - train_mean)/train_std

train_max = train_images.max()

train_images = train_images/train_max

test_mean = raw_test_images.mean()

test_std = raw_test_images.std()

test_images = (raw_test_images - test_mean)/test_std

test_max = test_images.max()

test_images = test_images/test_max

# Now let's plot the the histogram for the normalized dataset

axs[1].hist(train_images.flatten(), bins=20)

axs[1].set_title("Normalized Input Feature Distribution")

axs[1].set_xlabel("Feature Values")

axs[1].set_ylabel("Counts")

plt.show()

Let’s Define the Models¶

Our baseline model is a fully-connected network with ReLU activations. The output layer has 10 classes to generate logits for our class probabilities. The candidate is just the baseline with an additional dropout layer after each ReLU activation (except the final layer).

The dropout layer is placed after the ReLU activation because we want to only remove those neurons that participate in classifying an example. Removing neurons with zero or negative values will not serve this purpose. In fact, it may lead to ‘dead neurons’ which never activate.

from typing import Dict, Any

from functools import reduce

import operator

from flax import linen as nn

rng = jax.random.PRNGKey(RANDOM_KEY)

class MLP(nn.Module):

@nn.compact

def __call__(self, x, train: bool = True):

outputs = {}

x = nn.Dense(256)(x)

outputs['Dense_0'] = x

x = nn.BatchNorm(use_running_average=not train)(x)

outputs['BatchNorm_0'] = x

x = nn.relu(x)

outputs['Relu_0'] = x

x = nn.Dense(128)(x)

outputs['Dense_1'] = x

x = nn.BatchNorm(use_running_average=not train)(x)

outputs['BatchNorm_1'] = x

x = nn.relu(x)

outputs['Relu_1'] = x

x = nn.Dense(64)(x)

outputs['Dense_2'] = x

x = nn.BatchNorm(use_running_average=not train)(x)

outputs['BatchNorm_2'] = x

x = nn.relu(x)

outputs['Relu_2'] = x

x = nn.Dense(32)(x)

outputs['Dense_3'] = x

x = nn.BatchNorm(use_running_average=not train)(x)

outputs['BatchNorm_3'] = x

x = nn.relu(x)

outputs['Relu_3'] = x

x = nn.Dense(10)(x)

outputs['Dense_4'] = x

return x, outputs

# Initialize the candidate model

baseline_model = MLP()

dummy_input = jnp.ones((32, 32*32*3))

baseline_variables = baseline_model.init(rng, dummy_input, train=True)

baseline_params = baseline_variables['params']

baseline_batch_stats = baseline_variables['batch_stats']

dropout=0.4

class MLPDropout(nn.Module):

@nn.compact

def __call__(self, x, train: bool = True, rng = None):

outputs = {}

x = nn.Dense(256)(x)

outputs['Dense_0'] = x

x = nn.BatchNorm(use_running_average=not train)(x)

outputs['BatchNorm_0'] = x

x = nn.relu(x)

outputs['Relu_0'] = x

x = nn.Dropout(rate=0.4, deterministic=not train)(x, rng=rng)

outputs['Dropout_0'] = x

x = nn.Dense(128)(x)

outputs['Dense_1'] = x

x = nn.BatchNorm(use_running_average=not train)(x)

outputs['BatchNorm_1'] = x

x = nn.relu(x)

outputs['Relu_1'] = x

x = nn.Dropout(rate=0.3, deterministic=not train)(x, rng=rng)

outputs['Dropout_1'] = x

x = nn.Dense(64)(x)

outputs['Dense_2'] = x

x = nn.BatchNorm(use_running_average=not train)(x)

outputs['BatchNorm_2'] = x

x = nn.relu(x)

outputs['Relu_2'] = x

x = nn.Dropout(rate=0.2, deterministic=not train)(x, rng=rng)

outputs['Dropout_2'] = x

x = nn.Dense(32)(x)

outputs['Dense_3'] = x

x = nn.BatchNorm(use_running_average=not train)(x)

outputs['BatchNorm_3'] = x

x = nn.relu(x)

outputs['Relu_3'] = x

x = nn.Dropout(rate=0.2, deterministic=not train)(x, rng=rng)

outputs['Dropout_3'] = x

x = nn.Dense(10)(x)

outputs['Dense_4'] = x

return x, outputs

# Initialize the candidate model

candidate_model = MLPDropout()

dummy_input = jnp.ones((32, 32*32*3))

candidate_variables = candidate_model.init(rng, dummy_input, train=True, rng=rng)

candidate_params = candidate_variables['params']

candidate_batch_stats = candidate_variables['batch_stats']

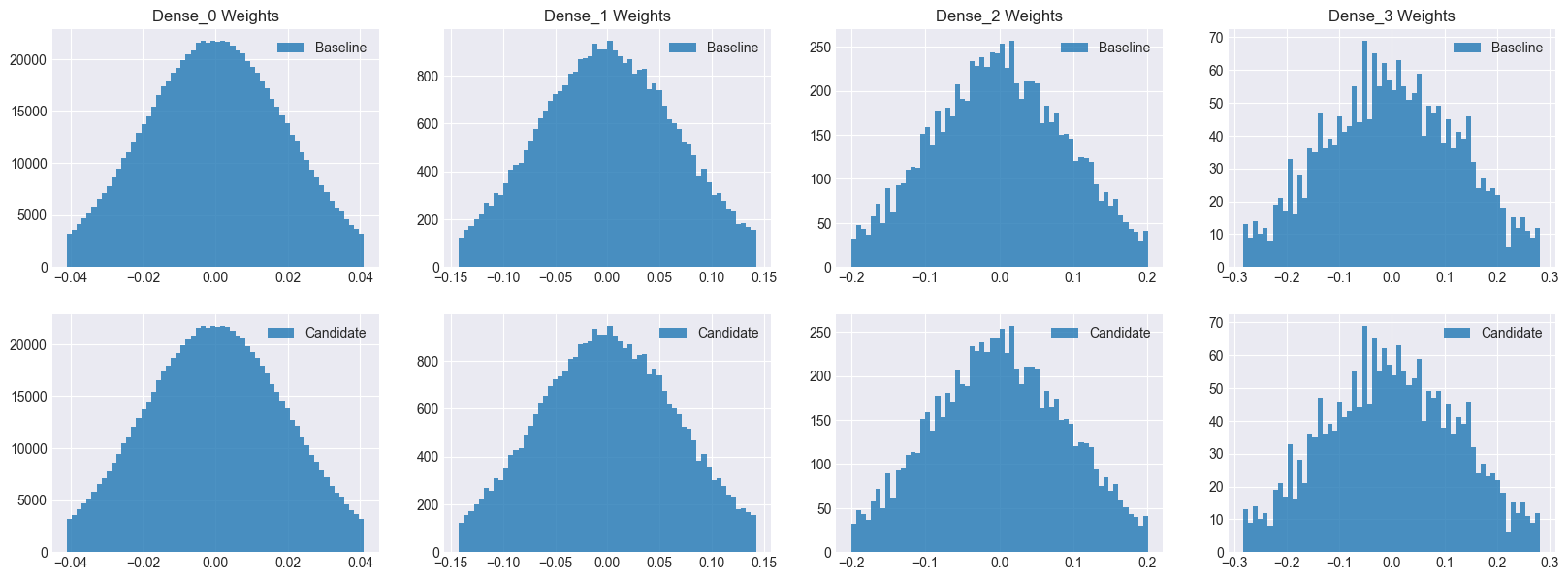

Let’s count the parameters and plot the initial distributions for the parameter values.¶

Show code cell source

# Count the # of model parameters

def count_params(params):

num_params = 0

for layer in params:

for key in params[layer]:

shape = params[layer][key].shape

num_params += reduce(operator.mul, shape)

return num_params

num_baseline_params = count_params(baseline_params)

num_candidate_params = count_params(candidate_params)

print(f"Number of baseline parameters: {num_baseline_params}")

print(f"Baseline P/S ratio: {num_baseline_params/train_images.shape[0]:0.4f}")

print(f"Number of candidate parameters: {num_candidate_params}")

print(f"Candidate P/S ratio: {num_candidate_params/train_images.shape[0]:0.4f}")

# Lets plot the initial baseline model weight distributions

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, 4, figsize=[20, 7])

baseline_dense0_w = baseline_params['Dense_0']['kernel'].flatten()

candidate_dense0_w = candidate_params['Dense_0']['kernel'].flatten()

baseline_dense1_w = baseline_params['Dense_1']['kernel'].flatten()

candidate_dense1_w = candidate_params['Dense_1']['kernel'].flatten()

baseline_dense2_w = baseline_params['Dense_2']['kernel'].flatten()

candidate_dense2_w = candidate_params['Dense_2']['kernel'].flatten()

baseline_dense3_w = baseline_params['Dense_3']['kernel'].flatten()

candidate_dense3_w = candidate_params['Dense_3']['kernel'].flatten()

axs[0,0].hist(baseline_dense0_w, bins=60, alpha=0.8)

axs[0,0].set_title("Dense_0 Weights")

axs[0,0].legend(["Baseline"])

axs[0,1].hist(baseline_dense1_w, bins=60, alpha=0.8)

axs[0,1].set_title("Dense_1 Weights")

axs[0,1].legend(["Baseline"])

axs[0,2].hist(baseline_dense2_w, bins=60, alpha=0.8)

axs[0,2].set_title("Dense_2 Weights")

axs[0,2].legend(["Baseline"])

axs[0,3].hist(baseline_dense3_w, bins=60, alpha=0.8)

axs[0,3].set_title("Dense_3 Weights")

axs[0,3].legend(["Baseline"])

axs[1,0].hist(candidate_dense0_w, bins=60, alpha=0.8)

axs[1,0].legend(["Candidate"])

axs[1,1].hist(candidate_dense1_w, bins=60, alpha=0.8)

axs[1,1].legend(["Candidate"])

axs[1,2].hist(candidate_dense2_w, bins=60, alpha=0.8)

axs[1,2].legend(["Candidate"])

axs[1,3].hist(candidate_dense3_w, bins=60, alpha=0.8)

axs[1,3].legend(["Candidate"])

plt.show()

Number of baseline parameters: 831210

Baseline P/S ratio: 16.6242

Number of candidate parameters: 831210

Candidate P/S ratio: 16.6242

As you can see, both models have the same number of parameters as well as initial distributions. Hence, we can safely assume that any performance improvement seen by the candidate model will be due to dropout.

Show code cell source

import os

import tempfile

import numpy as np

try:

type(tmpdir)

except:

base_temp_dir = tempfile.gettempdir()

tmpdir = os.path.join(base_temp_dir, "model_outputs")

os.makedirs(tmpdir, exist_ok=True)

def save_accuracy_to_disk(model, phase, metrics, tmpdir=tmpdir):

filename = f'{tmpdir}/{model}_{phase}_accuracy.npy'

jnp.save(filename, metrics)

def load_accuracy_from_disk(model, phase, tmpdir=tmpdir):

filename = f'{tmpdir}/{model}_{phase}_accuracy.npy'

if os.path.exists(filename):

return jnp.load(filename)

def save_outputs_to_disk(model, phase, epoch, outputs, tmpdir=tmpdir):

for key in outputs:

filename = f'{tmpdir}/{model}_{phase}_outputs_epoch_{epoch}_{key}.npz'

jnp.savez(filename, outputs[key])

def load_outputs_from_disk(model, phase, epoch, layer, tmpdir=tmpdir):

filename = f'{tmpdir}/{model}_{phase}_outputs_epoch_{epoch}_{layer}.npz'

if os.path.exists(filename):

return jnp.load(filename)['arr_0']

else:

#print(f"No data found for file {filename}")

return None

Show code cell source

try:

type(tmpdir)

except:

tmpdir = "/var/folders/x4/85_9sn3d1ng9q48ff6t3fw340000gn/T/model_outputs"

Let’s Train the Baseline Model¶

import optax

from flax.training import train_state

rng = jax.random.PRNGKey(RANDOM_KEY)

LR = 0.001

num_epochs = 200

batch_size = 32

# Create a train state

tx = optax.adam(learning_rate=LR)

baseline_ts = train_state.TrainState.create(apply_fn=baseline_model.apply, params=baseline_params, tx=tx)

def compute_loss(params, batch_stats, apply_fn, images, labels, train):

variables = {'params': params, 'batch_stats': batch_stats}

outputs, updated_variables = apply_fn(variables, images, train=train, mutable=['batch_stats'])

logits, _ = outputs

one_hot_labels = jax.nn.one_hot(labels, 10)

loss = optax.softmax_cross_entropy(logits, one_hot_labels).mean()

return loss, updated_variables['batch_stats']

@jax.jit

def train_step(state, batch_stats, images, labels):

def loss_fn(params):

return compute_loss(params, batch_stats, state.apply_fn, images, labels, train=True)

grads, updated_batch_stats = jax.grad(loss_fn, has_aux=True)(state.params)

state = state.apply_gradients(grads=grads)

return grads, state, updated_batch_stats

@jax.jit

def eval_step(state, batch_stats, images, labels):

variables = {'params': state.params, 'batch_stats': batch_stats}

logits, outputs = state.apply_fn(variables, images, train=False)

predictions = jnp.argmax(logits, axis=-1)

accuracy = jnp.mean(predictions == labels)

return accuracy, outputs

def train_and_evaluate(rng, ts, batch_stats, train_images, train_labels, test_images, test_labels):

num_train = train_images.shape[0]

train_accuracy, train_outputs = eval_step(ts, batch_stats, train_images, train_labels)

save_outputs_to_disk("Baseline", "train", "0", train_outputs)

train_outputs = None

test_outputs = None

test_accuracy, test_outputs = eval_step(ts, batch_stats, test_images, test_labels)

save_outputs_to_disk("Baseline", "test", "0", test_outputs)

train_accuracy_history = [train_accuracy]

test_accuracy_history = [test_accuracy]

print(f'Epoch 0, Train Accuracy: {train_accuracy:0.4f}, Test Accuracy: {test_accuracy:.4f}')

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

rng, sub_rng = jax.random.split(rng)

permutation = jax.random.permutation(sub_rng, num_train)

train_images = train_images[permutation]

train_labels = train_labels[permutation]

for i in range(0, num_train, batch_size):

batch_images = train_images[i:i + batch_size]

batch_labels = train_labels[i:i + batch_size]

grads, ts, batch_stats = train_step(ts, batch_stats, batch_images, batch_labels)

train_accuracy, train_outputs = eval_step(ts, batch_stats, train_images, train_labels)

test_accuracy, test_outputs = eval_step(ts, batch_stats, test_images, test_labels)

if epoch % 2 == 0:

save_outputs_to_disk("Baseline", "train", epoch+1, train_outputs)

save_outputs_to_disk("Baseline", "test", epoch+1, test_outputs)

if epoch % 50 == 0:

print(f'Epoch {epoch + 1}, Train Accuracy: {train_accuracy:0.4f}, Test Accuracy: {test_accuracy:.4f}')

train_accuracy_history.append(train_accuracy)

test_accuracy_history.append(test_accuracy)

train_outputs = None

test_outputs = None

print(f'Epoch {num_epochs}, Train Accuracy: {train_accuracy_history[-1]:0.4f}, Test Accuracy: {test_accuracy_history[-1]:.4f}')

save_accuracy_to_disk("Baseline", "train", train_accuracy_history)

save_accuracy_to_disk("Baseline", "test", test_accuracy_history)

train_and_evaluate(rng, baseline_ts, baseline_batch_stats, train_images, train_labels, test_images, test_labels)

Epoch 0, Train Accuracy: 0.1096, Test Accuracy: 0.1108

Epoch 1, Train Accuracy: 0.4692, Test Accuracy: 0.4593

Epoch 51, Train Accuracy: 0.9252, Test Accuracy: 0.5441

Epoch 101, Train Accuracy: 0.9718, Test Accuracy: 0.5348

Epoch 151, Train Accuracy: 0.9854, Test Accuracy: 0.5276

Epoch 200, Train Accuracy: 0.9921, Test Accuracy: 0.5258

Next, Let’s Train the Candidate Model¶

# Create a train state

tx = optax.adam(learning_rate=LR)

candidate_ts = train_state.TrainState.create(apply_fn=candidate_model.apply, params=candidate_params, tx=tx)

def compute_loss(params, batch_stats, apply_fn, images, labels, train, rng):

variables = {'params': params, 'batch_stats': batch_stats}

outputs, updated_variables = apply_fn(variables, images, train=train, rng=rng, mutable=['batch_stats'])

logits, _ = outputs

one_hot_labels = jax.nn.one_hot(labels, 10)

loss = optax.softmax_cross_entropy(logits, one_hot_labels).mean()

return loss, updated_variables['batch_stats']

@jax.jit

def train_step(state, batch_stats, images, labels, rng):

def loss_fn(params):

return compute_loss(params, batch_stats, state.apply_fn, images, labels, train=True, rng=rng)

grads, updated_batch_stats = jax.grad(loss_fn, has_aux=True)(state.params)

state = state.apply_gradients(grads=grads)

return grads, state, updated_batch_stats

@jax.jit

def eval_step(state, batch_stats, images, labels, rng):

variables = {'params': state.params, 'batch_stats': batch_stats}

logits, outputs = state.apply_fn(variables, images, train=False, rng=rng)

predictions = jnp.argmax(logits, axis=-1)

accuracy = jnp.mean(predictions == labels)

return accuracy, outputs

def train_and_evaluate(rng, ts, batch_stats, train_images, train_labels, test_images, test_labels):

num_train = train_images.shape[0]

train_accuracy, train_outputs = eval_step(ts, batch_stats, train_images, train_labels, rng)

save_outputs_to_disk("Candidate", "train", "0", train_outputs)

test_accuracy, test_outputs = eval_step(ts, batch_stats, test_images, test_labels, rng)

save_outputs_to_disk("Candidate", "test", "0", test_outputs)

print(f'Epoch 0, Train Accuracy: {train_accuracy:0.4f}, Test Accuracy: {test_accuracy:.4f}')

train_accuracy_history = [train_accuracy]

test_accuracy_history = [test_accuracy]

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

rng, sub_rng = jax.random.split(rng)

permutation = jax.random.permutation(sub_rng, num_train)

train_images = train_images[permutation]

train_labels = train_labels[permutation]

for i in range(0, num_train, batch_size):

batch_images = train_images[i:i + batch_size]

batch_labels = train_labels[i:i + batch_size]

grads, ts, batch_stats = train_step(ts, batch_stats, batch_images, batch_labels, sub_rng)

train_accuracy, train_outputs = eval_step(ts, batch_stats, train_images, train_labels, sub_rng)

test_accuracy, test_outputs = eval_step(ts, batch_stats, test_images, test_labels, sub_rng)

if epoch % 2 == 0:

save_outputs_to_disk("Candidate", "train", epoch+1, train_outputs)

save_outputs_to_disk("Candidate", "test", epoch+1, test_outputs)

if epoch % 50 == 0:

print(f'Epoch {epoch + 1}, Train Accuracy: {train_accuracy:0.4f}, Test Accuracy: {test_accuracy:.4f}')

train_accuracy_history.append(train_accuracy)

test_accuracy_history.append(test_accuracy)

save_accuracy_to_disk("Candidate", "train", train_accuracy_history)

save_accuracy_to_disk("Candidate", "test", test_accuracy_history)

print(f'Epoch {num_epochs}, Train Accuracy: {train_accuracy_history[-1]:0.4f}, Test Accuracy: {test_accuracy_history[-1]:.4f}')

train_and_evaluate(rng, candidate_ts, candidate_batch_stats, train_images, train_labels, test_images, test_labels)

Epoch 0, Train Accuracy: 0.1096, Test Accuracy: 0.1108

Epoch 1, Train Accuracy: 0.4253, Test Accuracy: 0.4278

Epoch 51, Train Accuracy: 0.6953, Test Accuracy: 0.5547

Epoch 101, Train Accuracy: 0.7653, Test Accuracy: 0.5547

Epoch 151, Train Accuracy: 0.8072, Test Accuracy: 0.5597

Epoch 200, Train Accuracy: 0.8342, Test Accuracy: 0.5558

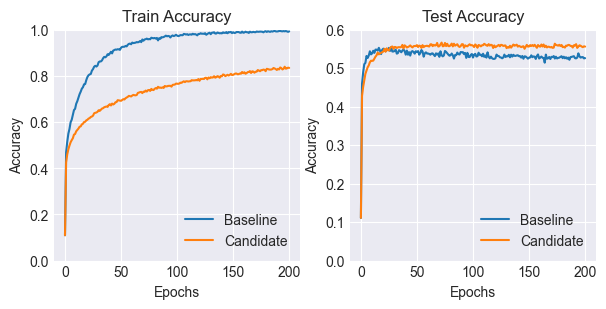

Let’s look at the accuracy metrics over time.

Show code cell source

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1,2, figsize=[7,3])

baseline_train_accuracy_history = load_accuracy_from_disk("Baseline", "train")

baseline_test_accuracy_history = load_accuracy_from_disk("Baseline", "test")

candidate_train_accuracy_history = load_accuracy_from_disk("Candidate", "train")

candidate_test_accuracy_history = load_accuracy_from_disk("Candidate", "test")

axes[0].plot(baseline_train_accuracy_history)

axes[0].plot(candidate_train_accuracy_history)

axes[0].set_title("Train Accuracy")

axes[0].legend(["Baseline", "Candidate"])

axes[0].set_xlabel("Epochs")

axes[0].set_ylabel("Accuracy")

axes[0].set_ylim(0,1.0)

axes[1].plot(baseline_test_accuracy_history)

axes[1].plot(candidate_test_accuracy_history)

axes[1].set_title("Test Accuracy")

axes[1].legend(["Baseline", "Candidate"])

axes[1].set_xlabel("Epochs")

axes[1].set_ylabel("Accuracy")

axes[1].set_ylim(0,0.6)

plt.show()

As you can see, the candidate model with the dropout layers performs better than the baseline. It also takes longer to converge than the baseline.

So Why Does Dropout Help?¶

Regularization / Noise Addition¶

Notice that the baseline model tends to overfit considerably more on the training data, reaching a training accuracy of 99%, but lagging behind the candidate in terms of test set performance.

This is because dropout can be seen as a way of adding noise, which prevents the model from overfitting to the specific training examples and forces it to learn more general patterns, thus improving test performance.

It can also be seen as a form of regularization, which means that the addition of noise makes the model more robust to small changes in the input distribution.

Sparse Activations¶

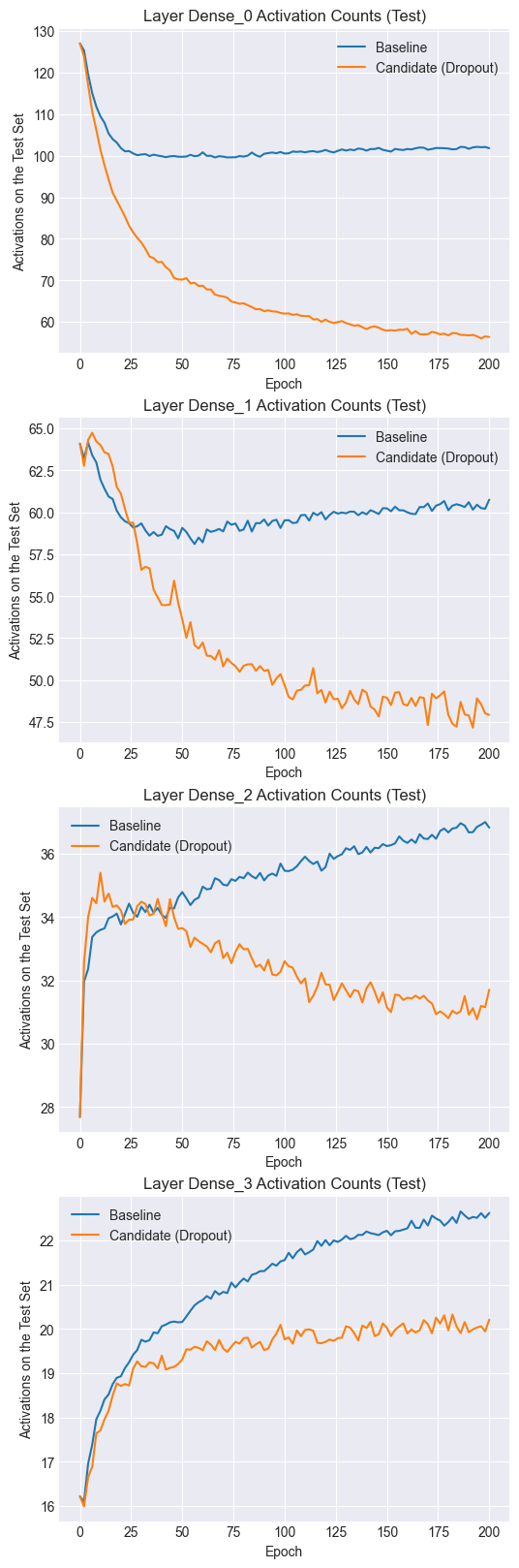

Let’s plot the number of activated neurons per training example over time.

Show code cell source

def get_activation_stats(model, phase, layer):

baseline_activation_counts = []

baseline_dead_neuron_counts = []

for i in range(num_epochs):

baseline_outputs = load_outputs_from_disk(model, phase, i, layer)

if baseline_outputs is not None:

baseline_datapoints = baseline_outputs.shape[0]

active_baseline_outputs = baseline_outputs[baseline_outputs > 0]

bcount = active_baseline_outputs.flatten().shape[0]/baseline_datapoints

baseline_activation_counts.append(bcount)

return baseline_activation_counts, baseline_dead_neuron_counts

fix, ax = plt.subplots(4, 1, figsize=[6,5*4])

for layer in range(4):

baseline_test_activation_counts, baseline_test_dead_neuron_counts = get_activation_stats("Baseline", "test", f"Relu_{layer}")

candidate_test_activation_counts, candidate_test_dead_neuron_counts = get_activation_stats("Candidate", "test", f"Dropout_{layer}")

ax[layer].plot(range(0, 201, 2), baseline_test_activation_counts)

ax[layer].plot(range(0, 201, 2), candidate_test_activation_counts)

ax[layer].set_title(f"Layer Dense_{layer} Activation Counts (Test)")

ax[layer].set_xlabel("Epoch")

ax[layer].set_ylabel("Activations on the Test Set")

ax[layer].legend(["Baseline", "Candidate (Dropout)"])

plt.show()

Notice that both the baseline and candidate models have similar numbers of activated neurons at the start of training. However, as training progresses, the candidate model tends to have fewer activations per training example. Dropout thus encourages sparse representations, which, as we saw in the results, also tend to be more robust to changes in the inputs (i.e. regularization).

In the baseline model, a neuron tends to co-adapt to other specific neurons, which leads to overfitting. By using dropout, a neuron cannot necessarily depend on other units and has to individually learn a more robust function.

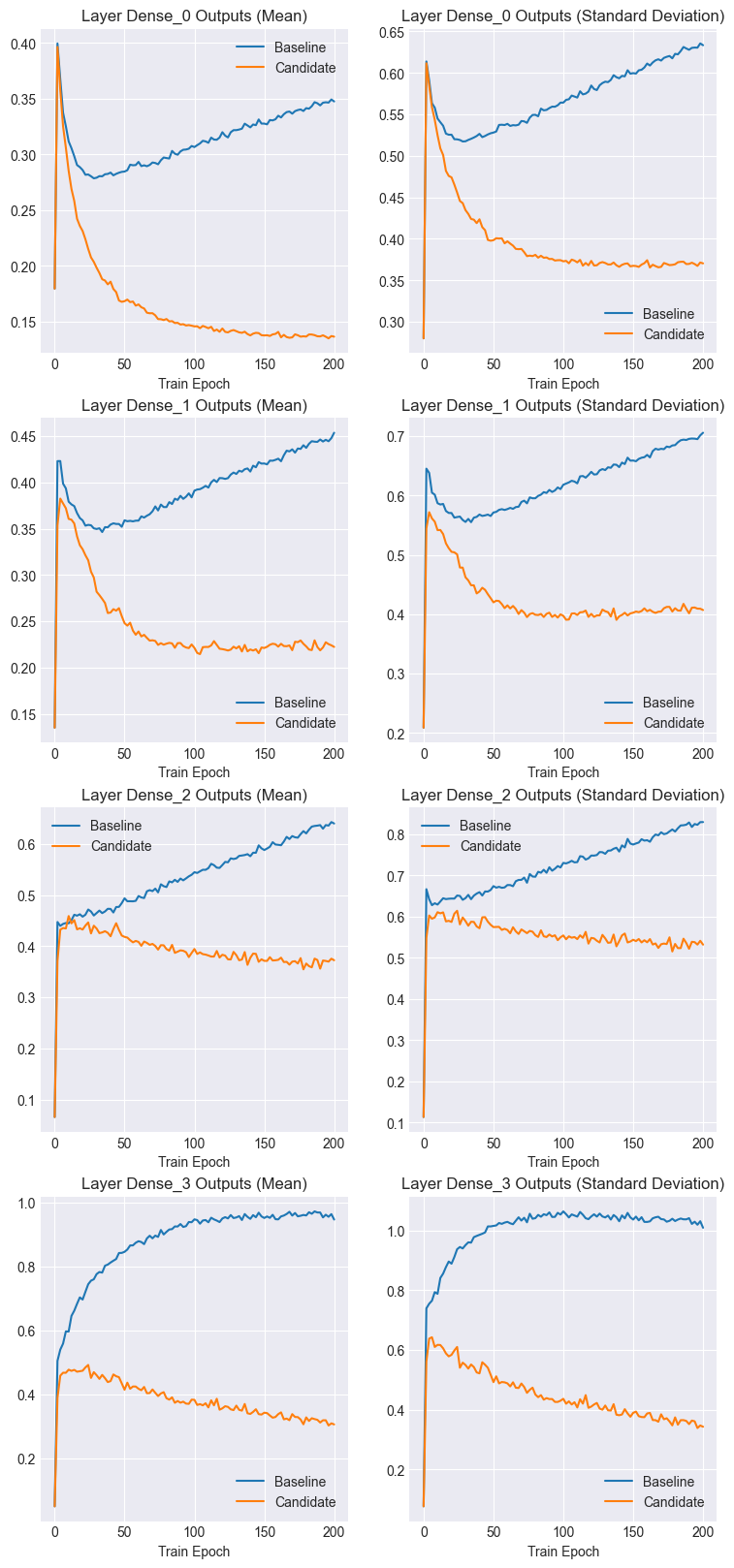

Next, let’s look at the activation statistics.

Show code cell source

fig, axs = plt.subplots(4, 2, figsize=(9,5*4))

for l in range(4):

baseline_output_means = []

baseline_output_stds = []

candidate_output_means = []

candidate_output_stds = []

for i in range(num_epochs):

baseline_o1 = load_outputs_from_disk("Baseline", "train", i, f"Relu_{l}")

if baseline_o1 is not None:

baseline_m1 = baseline_o1.mean()

baseline_output_means.append(baseline_m1)

baseline_s1 = baseline_o1.std()

baseline_output_stds.append(baseline_s1)

candidate_o1 = load_outputs_from_disk("Candidate", "train", i, f"Dropout_{l}")

if candidate_o1 is not None:

candidate_m1 = candidate_o1.mean()

candidate_output_means.append(candidate_m1)

candidate_s1 = candidate_o1.std()

candidate_output_stds.append(candidate_s1)

axs[l,0].set_title(f"Layer Dense_{l} Outputs (Mean)")

axs[l,0].set_xlabel("Train Epoch")

axs[l,0].plot(range(0,201,2),baseline_output_means)

axs[l,0].plot(range(0,201,2),candidate_output_means)

axs[l,1].set_title(f"Layer Dense_{l} Outputs (Standard Deviation)")

axs[l,1].set_xlabel("Train Epoch")

axs[l,1].plot(range(0,201,2),baseline_output_stds)

axs[l,1].plot(range(0,201,2),candidate_output_stds)

axs[l,0].legend(["Baseline", "Candidate"])

axs[l,1].legend(["Baseline", "Candidate"])

plt.show()

Notice that both the mean and standard deviation of the baseline activations increase as training progressses. However, the candidate activation statistics tend to stabilize and even decrease.

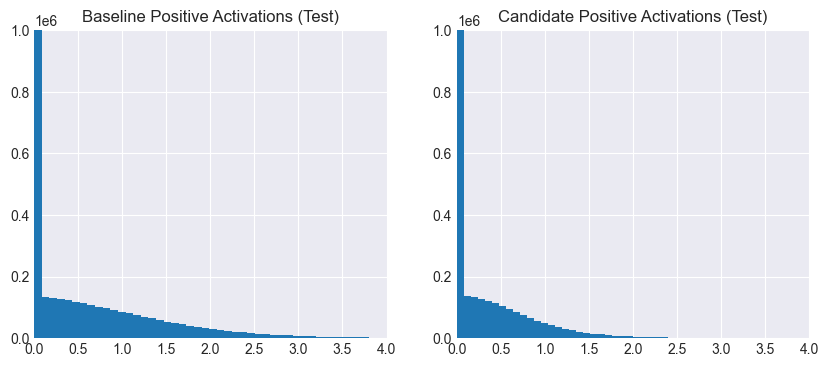

Let’s confirm this by comparing activation histograms.

Show code cell source

baseline_all_outputs = []

candidate_all_outputs = []

num_epochs = 200

for l in range(4):

outputs = load_outputs_from_disk("Baseline", "test", num_epochs-1, f"Relu_{l}").flatten()

baseline_all_outputs.append(outputs)

outputs = load_outputs_from_disk("Candidate", "test", num_epochs-1, f"Relu_{l}").flatten()

candidate_all_outputs.append(outputs)

baseline_all_outputs = jnp.concat(baseline_all_outputs, axis=0)

candidate_all_outputs = jnp.concat(candidate_all_outputs, axis=0)

Show code cell source

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=[10,4])

axs[0].hist(baseline_all_outputs, bins=100)

axs[0].set_xlim(0.00,4.0)

axs[0].set_ylim(0,1e6)

axs[0].set_title("Baseline Positive Activations (Test)")

axs[1].hist(candidate_all_outputs, bins=100)

axs[1].set_xlim(0.00,4.0)

axs[1].set_ylim(0,0.1e7)

axs[1].set_title("Candidate Positive Activations (Test)")

plt.show()

It’s clear that the baseline activations are more spread out than the candidate ones, which are more sparse and smaller in magnitude. Thus, not only are fewer neurons activated per example, but the magnitudes of the activations themselves are diminished. This is due to the network having learned to avoid overly depending on specific neurons across training examples.

Ensembling¶

Dropout can also be seen as a way of creating an ensemble of models with shared weights. Mathematically, a single neural network with dropout is an ensemble of \(2^n\) models, where \(n\) is the number of neurons. Each model in this ensemble is selected for a training step with a probability of \((1-p)^k\), where \(k\) is the size of the model.

In the light of this, we can explain the fewer and sparser activations as smaller sub-networks specializing in recognizing specific types of examples.

References:¶

Srivastava, N., Hinton, G., Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., & Salakhutdinov, R. (2014). Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 15(1).

Baldi, P., & Sadowski, P. (2013). Understanding dropout. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 26.

Sutskever, I., Martens, J., Dahl, G., & Hinton, G. (2013). On the importance of initialization and momentum in deep learning. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-13).

Nair, V., & Hinton, G. E. (2010). Rectified linear units improve restricted Boltzmann machines. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-10).